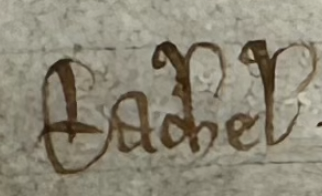

Rachel Lumbard of Nottingham

Referred to in records as: “filia sua”, “Rachel”, “Rachel fil Dauid”, “Rachel fil’ Dauid”, “Rachel of Nottingham”, “Rachelʼ”, “Rachelʼ Notingʼ”.

Brief biography

Rachel was the daughter of David Lumbard, chirographer

of Nottingham from 1230–1231 and later its ballivus (bailiff or royal

official, head of the Nottingham Jewish community). Along with her father and brothers

Moses and Amiot, she

worked as a financier from the 1230s to the 1250s. There is no evidence that she ever

married or had children, and she was likely dead by the mid 1250s. She first appears

in

surviving records in 1232, already an adult, in a royal order to extract from the

Nottingham archa (chest holding Jewish bonds) any documents or tally sticks showing

transactions between Hugh Tothill, son of the parson of Carlton (Notts), and David,

Moses, or Rachel. In 1236, the king ordered a survey of lands in Aylestone

(Leics) that were held in pledge by Rachel and her brother Moses. This early partnership

with her father and Moses suggests that Rachel should not be excluded from the

affections and associations that have sometimes been attributed to father and son

exclusively.

By the 1240s, Rachel worked with her brother Amiot, elected

chirographer in 1241, and his daughter Murielda. The Plea Rolls of the Exchequer

of the Jews show Rachel managing three debts with him in this period, totalling more

than £42. By 1245, she was an independent creditor to three Christian men, one of

these

debts acknowledged through a Hebrew starr written for her by Amiot. In the same year,

the Justices of the Exchequer of the Jews at Westminster sent twelve of her chirographs

to the sheriff of Nottingham, who was to seize the debtors’ property until they paid

her. While this trajectory shows a maturing businesswoman, functioning independently

if

within a wealthy family network, Rachel was likely taxed out of business, as were

many

from 1241 to 1255 when King Henry III’s brutal taxation of English Jews was at

its peak. Rachel, ultimately, was also beholden to her male relatives. The 1245 scrutiny

of her debts, for example, was undertaken because she owed £12 towards the king’s

£10,000 tallage of 1246. While this is not an insignificant percentage for a single

woman, an endorsement of the Justices’ order shows that she was only able to collect

about £8, and that the collected money was to go to her brothers to contribute to

the

family’s obligations.

When debts in the Nottingham archa were seized by royal order in

1251, Rachel had just five bonds, with a local Christian butcher, goldsmith, and

citizen, and with two men from Ratcliffe-on-Soar (Notts). She is not mentioned

again after this and probably died sometime between 1251 and 1255: in 1255, her brother

Amiot released Thomas Brien of Ratcliffe-on-Soar, one of the men to whom Rachel was

a

creditor in 1251, from all debts owed to the family. By 1262, when the Nottingham

archa

was once again scrutinized, only a single family bond remained: that of Rachel’s

sister-in-law Ivette, Moses’ widow.

Further reading

- Hillaby, J. and C. Hillaby, The Palgrave Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History. London: Palgrave. 2015, s.v. The English Medieval Jewry, c.1075–1290: The Impoverishment of the Jewry, 1241–55 and Nottingham: David Lumbard and Family, 1230–55, pp. 7–9 and 291.

- Olszowy-Schlanger, J., ed. Hebrew and Hebrew-Latin Documents from Medieval England: A Diplomatic and Palaeographical Study. Volume 1. Turnhout: Brepols. 2015, nos. 13, 46, and 55.

- Olszowy-Schlanger, J., ed. Hebrew and Hebrew-Latin Documents from Medieval England: A Diplomatic and Palaeographical Study. Volume 2. Turnhout: Brepols. 2015, no. 155.

- The National Archives of the UK (TNA), DL 25/2381, DL 25/2382/2068, and E 40/14957.

Dates mentioned in records

1221–1251

Locations

Surrey, Nottinghamshire

Relatives

- Amiot father of Murielda (brother)

- David Lumbard father of Rachel (father)

- Moses son of David Lumbard (brother)

- Isaac son of Moses Lumbard (nephew)

- Unnamed daughter of Moses Lumbard (niece)

Records

- 1221: Donum/Tallage

- 1232, Nottinghamshire: Debt

- 1233: Donum/Tallage

- 1236, Nottinghamshire: Property, Debt

- 1244, Surrey: Debt

- 1244–1245, Nottinghamshire: Debt

- 1245, Nottinghamshire: Debt

- 1245, Nottinghamshire: Debt

- 1246–1247, Nottinghamshire: Donum/Tallage

- 1247, Nottinghamshire: Debt

- 1250, Nottinghamshire: Audit of chest

- 1251, Nottinghamshire: Debt, Audit of chest