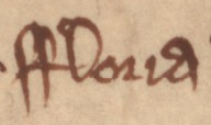

Floria Tapay

Traits

- Convert to Christianity

Brief biography

Floria Tapay was the wife of Solomon Tapay, also called Solomon de Brubrok’ (a name that perhaps points to an origin in Braybrooke,

Northamptonshire). Floria resided in Oxford, and she converted to Christianity in

1280 along with the sisters Belaset and Hittecote of Oxford, to whom she may have been related. Her husband was dead by the summer of 1280, when

the Justices of the Exchequer of the Jews ordered a mixed jury of Christians and Jews

to convene and assess the value of the converts’ belongings. In spring 1281 her husband

was named, along with other Oxford Jews, in a writ brought by Alan de Shescote, a

monk at Bruern Abbey in West Oxfordshire. Alan de Shescote claimed that Solomon and

other Oxford Jewish men had broken the king’s peace by taking certain documents and

goods from him while he was in the city. Solomon, of course, could not be found (nor

could his associates), and it appears that the neither the sheriff of Berkshire and

Oxfordshire (at the time John de Tidmarsh) nor the Justices were yet aware of Solomon’s

death. Belaset of Oxford, who converted with Floria, lost her husband in the coin-clipping

crisis of the late 1270s, when many English Jews were imprisoned and executed for

allegedly trimming metal from the outer edges of coins to illegally mint new ones

or sell the metal, and Floria’s situation may have been the same. However, unlike

the women with whom she converted, Floria cannot be traced beyond the orders to assess

her pre-conversion estate. Though Belaset and her sister Hittecote had moved to the

London Domus Conversorum (House of Converts) by the spring of 1281, Floria’s whereabouts after 1280 are unknown;

she likely took a Christian name shortly after her conversion.

A group of women converting together is notably unique. Floria’s case suggests that

women might embrace such a change together, particularly if widowhood and collective

loss left few other options.

Further reading

- Fogle, Lauren, The King’s Converts: Conversion in Medieval London. Lexington Books. 2019.

- Hillaby, J. and C. Hillaby, The Palgrave Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History. London: Palgrave. 2015, s.v. Coinage and Coin-Clipping Crises, 1238–47 and 1276–79, pp. 104–09.

Dates mentioned in records

1280

Locations

Oxfordshire